C. Carey Cloud » Articles » Carey Cloud reminisces on his successful career

Cloud Nine: Brown County artist Carey Cloud reminisces on his successful career

"I always had talent," explains gentle-mannered C. Carey Cloud, the artist.

"I was born an artist."

Completing his memoirs, titled "Cloud Nine," to be released in May, Cloud recently recalled his childhood and his first art work.

"I designed a big sun on a varnished cupboard with a nail, engraving it with the sun's rays out from it."

"It was beautiful," he mused, "but my father didn't appreciate it. It's the only time I can remember that he spanked me on the rear."

An illustration on the cover for "Cloud Nine" depicts that young boy alone hoeing corn. His father and brother have gone inside for dinner.

"My father explained to me, ‘Son, you're always gonna have to hoe out your own row.' "

"I'll have to do it myself" became a motto for Cloud.

Fortunately for millions of Cracker Jacks eaters, Cloud's creative nature was not stemmed by the parental reaction to his first artistic endeavor.

Cloud created millions of toys that were packaged within the brightly-colored candy boxes.

A lot of work and hardship preceded success for the farmer's son who dropped out of grade school and went on to become a well-known artist.

Cloud was married at an early age to the late Vera Nickerson. World War I forced the couple to move from Northern Indiana to Cleveland. During Cloud's employment in a steel mill there, daughter Mary was born.

"After World War I, I worked in a piano factory," he remembers.

"My family was poor. Today, we'd be below the poverty level."

Money saved from the piano-factory job allowed him to enroll in a $25 correspondence art course.

Cloud's first commercial-art assignment recouped the art-class- enrollment fee. That project created the packaging for Charles C. Deam's Meat Smoke, a hickory-seasoning used to flavor meat cooked indoors.

"After that, I walked the streets and starved." The family now included son Harold, who died in 1960.

Employment finally came with the Cleveland Press designing newspaper advertisements.

Addition of the couple's third child, Don, came prior to Cloud's opportunity to double his pay. That advertising venture led to other successes.

The family moved to Brown County, where Cloud wrote a cartoon feature similar to the Abe Martin series.

He also produced illustrations, including cowboys for Blue Book magazine.

His inventiveness also paid off in a successful pop-up-book design he patented and in a Superman Game, manufactured and shipped from Morgantown.

The Depression halted both these successes and the family's 3-year stay in Brown County.

The couple lost its home and was forced to move to Chicago. Payment of a debt to the family eased their financial burdens.

Steady employment with the advertising department of Cracker Jacks brought relief.

That early nail-engraved sun finally began to shine in 1937.

The Cracker Jacks company's desire to move away from the Japanese manufacturing of their toys opened "the beginning of a beautiful relationship" for Cloud.

At the insistence of a fellow worker, Cloud pursued the opportunity to produce the company's toys.

His father's early advice—"do it on your own"—became a necessity.

The problems of production seemed minor when compared with his lack of financing. Cloud's inadequate savings forced him to convince his suppliers to forward the necessary materials on credit.

"No one turned me down," he says. Cloud the toy-designer spent the next 29 years in that endeavor.

"Many are still my good friends today," he said of his trusting creditors.

The first order Cloud produced on his own for Cracker Jacks, nodding- head tin animals, numbered six million.

The most rewarding design for the total 895 million toys he produced for Cracker Jacks remains the "dolls of the nations."

Made of molded plastic, the dolls numbered 45 million with an original tooling cost of $13,000.

Of those years, Cloud says "The stories were the best."

The artist still chuckles over a cab driver who thought he was Superman.

"He hugged me and couldn't wait to tell his children that I rode in his cab.

"A friend and I were discussing my Superman game. I couldn't disappoint the cabbie, so I didn't tell him otherwise."

During World War II, the government halted production of the Cracker Jacks toys.

Soldiers stationed in the Pacific petitioned the US government to return the toys to their rightful place in the Cracker Jacks boxes.

The soldiers won, and the toys—fake coins—reappeared.

The coins were produced by two gravity-fed machines, stamping metal scrap, obtained from the Ball Brothers Canning Company.

Sayings on the coins read "Daffy Dollar, Goofy Coin, and Lucky Pieces."

It took the Ball Brothers company until 1948 to discover how Cloud used the scrap.

The company responded by trying to raise the price of the scrap from $25 to $125 a ton. Instead, Cloud ceased manufacturing the coins, saying "they'd run their course."

In 1965, the Cracker Jacks toy man decided to retire. Thinking he was "getting old," Cloud focused his creativity on painting.

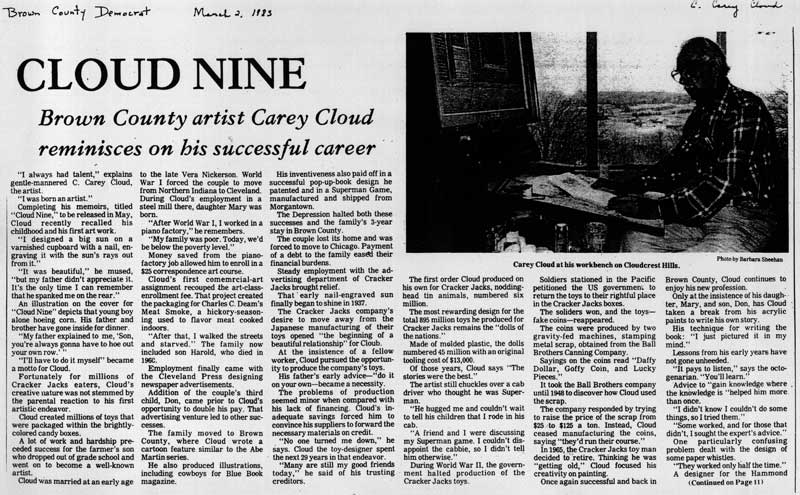

Once again successful and back in Brown County, Cloud continues to enjoy his new profession.

Only at the insistence of his daughter, Mary, and son, Don, has Cloud - taken a break from his acrylic paints to write his own story.

His technique for writing the book: "I just pictured it in my mind."

Lessons from his early years have not gone unheeded.

"It pays to listen," says the octogenarian. "You'll learn."

Advice to "gain knowledge where the knowledge is "helped him more than once.

"I didn't know I couldn't do some things, so I tried them." "Some worked, and for those that didn't, I sought the expert's advice."

One particularly confusing problem dealt with the design of some

paper whistles.

"They worked only half the time."

A designer for the Hammond Organ Company solved the problem.

Other similar problems were solved by going to an expert.

"There is nothing I would change if I could do it again," Cloud says.

The loss of his wife and a son would be exceptions.

'Everything I did was building character, building up to something.

"Each step meant something, each regress was a progress, though maybe I didn't know it at the time."

For Cloud, life on "Cloud Nine" has several meanings.

The physical placement of his home/studio in Cloudcrest Hills overlooking Nashville sometimes leaves the author staring out over Salt Creek through the low-lying fog.

More significant, however, is C. Carey Cloud, the nine-year-old boy hoeing that long row of corn. His transition from that youth to his present life matches the U.S. Weather Service's definition of "Cloud Nine."

"Everything's rosy and happy when you're on 'Cloud Nine,' "says the artist.

Excitement for both his life and his book continue to build.

Already the author has sold more than half of the first 1,000 numbered and autographed copies.

He envisions the remainder of the special edition will be committed prior to a show of hi paintings and an open house to be held at the Brown County Art Gallery on May 15.

—Barbara Sheehan