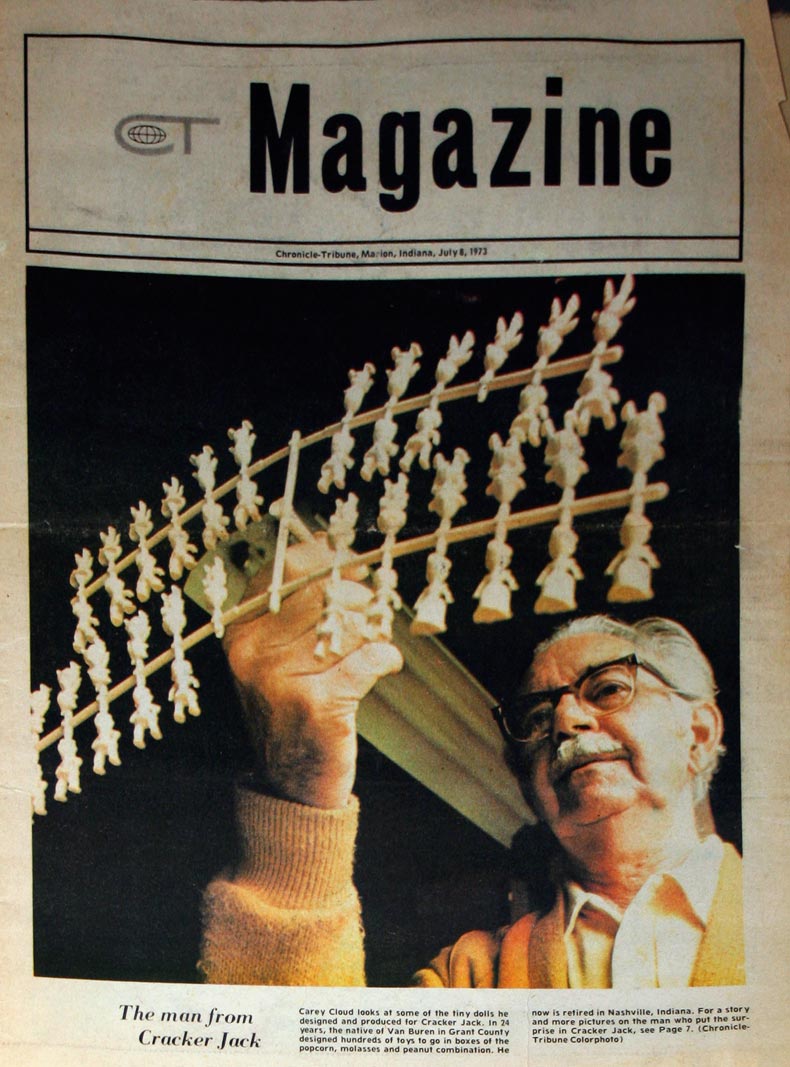

C. Carey Cloud » Articles » The Man Who Gave Us Cracker Jack Toys

Larger images below

The Man Who Gave Us Cracker Jack Toys

by Dick Martin

Chronicle-Tribune Magazine

July 8, 1973

Carey Cloud — a man who makes Santa Claus look like a piker — can look back these days on his 24 years of toymaking and smile with satisfaction.

"I didn't know I had a child's mind," he says. But the 74-year-old native of Grant County combined his ability to think up tiny inexpensive toys with a shrewd business sense for a most unique career.

Carey Cloud, made a toy for you.

And you got it "free."

For Carey Cloud is the man who designed and manufactured the toys that appeared in Cracker Jack boxes.

He began making them in 1938 and retired in 1965.

He estimates that in one year he manufactured 45 million toys for Crackers Jacks. If each child who got one of the toys played with it for 10 minutes, Cloud says he figures he provided 7½ million play-hours for kids in that one year alone.

Cracker Jack began in 1872 when F. W. Rueckheim, a German immigrant, operated a popcorn stand in Chicago during the city's rebuilding days after the Great Chicago Fire.

Sometime later he concocted a mixture of molasses, popcorn and peanuts that was a hit at the Chicago World's Fair of 1893. By 1896 he had found a method to keep the molasses from forming the popcorn and peanuts into a sticky mess.

Legend has, it that the name of the product developed when a salesman sampled a handful of the candy and remarked that it sure was a "Cracker Jack!", 1890s slang for a sure-fire marketing hit.

For several years after 1910 each Cracker Jack box carried a coupon that could be redeemed for premiums. In 1927 coupons were discontinued and a small prize was placed in each box.

Cracker Jack is still made in Chicago and the recipe is closely guarded as a secret. But company officials will admit the firm is the world's largest user of popcorn — 25 tons a day.

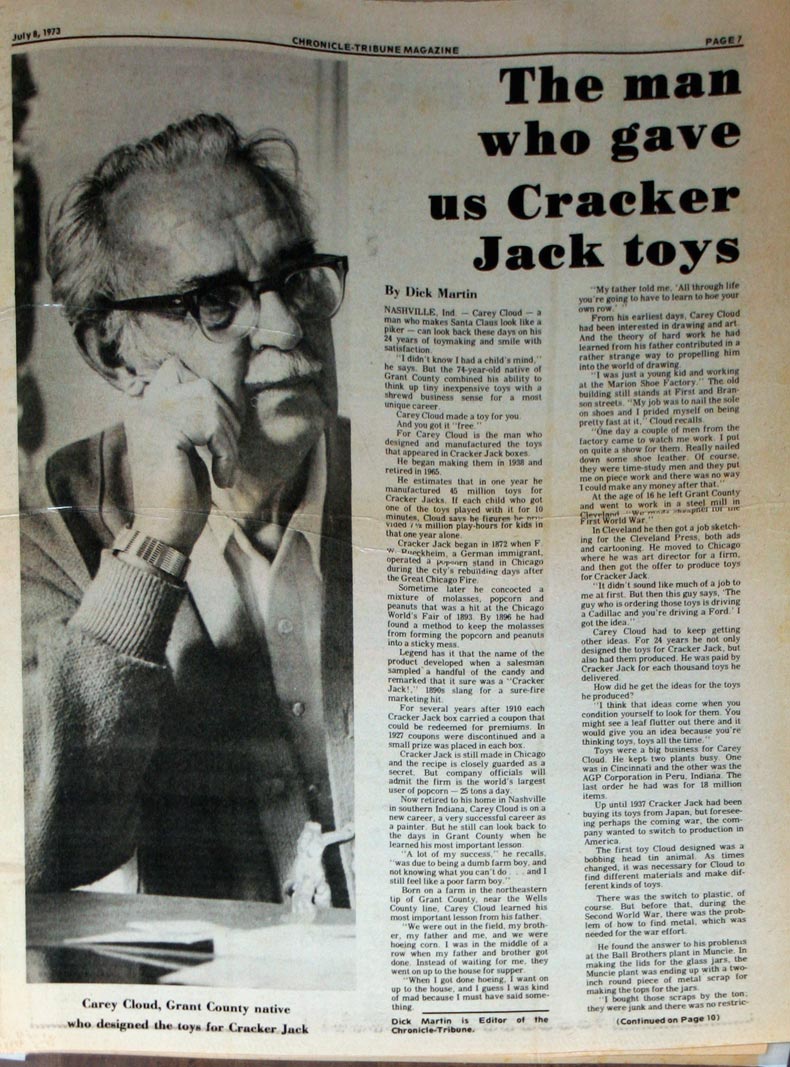

Now retired to his home in Nashville in southern Indiana, Carey Cloud is on a new career, a very successful career as a painter. But he still can look back to the days in Grant County when he learned his most important lesson.

"A lot of my success," he recalls, "was due to being a dumb farm boy, and not knowing what you can't do... and I still feel like a dumb farm boy."

Born on a farm in the north-eastern tip of Grant County, near the Wells County line, Carey Cloud learned his most important lesson from his father.

"We were out in the field, my brother, my father and me, and we were hoeing

corn. I was in the middle of a row when my father and brother got done. Instead of waiting for me, they went up to the house for supper.

"When I got done hoeing, I went on up to the house, and I guess I was kind of mad because I must have said something.

"My father told me, "All through life you're going to have to learn to hoe your own row."

From his earliest days, Carey Cloud had been interested in drawing and art. And the theory of hard work he had learned from his father contributed in a rather strange way to propelling him into the world of drawing.

"I was just a young kid and working at the Marion Shoe Factory." The old building still stands at First and Branson streets. "My job was to nail the sole on shoes and I prided myself on being pretty fast at it," Cloud recalls.

"One day a couple of men from the factory came to watch me work. I put on quite a show for them. Really nailed down some shoe leather. Of course, they were time-study men and they put me on piece work and there was no, way I could make any money after that."

At the age of 16 he left Grant County and went to work in a steel mill in Cleveland, "We made shrapnel for the First World War."

In Cleveland, he then got a job sketching for the Cleveland Press, both ads and cartooning. He moved to Chicago where he was art director for a firm, and then got the offer to produce toys for Cracker Jack.

"It didn't sound like much of a job to me, at first. But then this guy says, 'The guy who is

ordering those toys is driving a Cadillac and you're driving a Ford.' I got the idea."

Carey Cloud had to keep getting other ideas. For 24 years he not only designed the toys for Cracker Jack, but he also had them produced. He was paid by Cracker Jack for each thousand toys he delivered.

How did he get the ideas for the toys he produced?

"I think the ideas come when you condition yourself to look for them. you might see a leaf flutter out there and it would give you an idea

because you're thinking toys, toys all the time."

Toys were big business for Carey Cloud. He kept two plants busy. One in

Cincinnati and the other was the AGP Corporation in Peru, Indiana. The last order he had was for 18 million items.

Up until 1937 Cracker Jack had been buying its toys from Japan, but

foreseeing perhaps the coming war, the company wanted to switch to production in America.

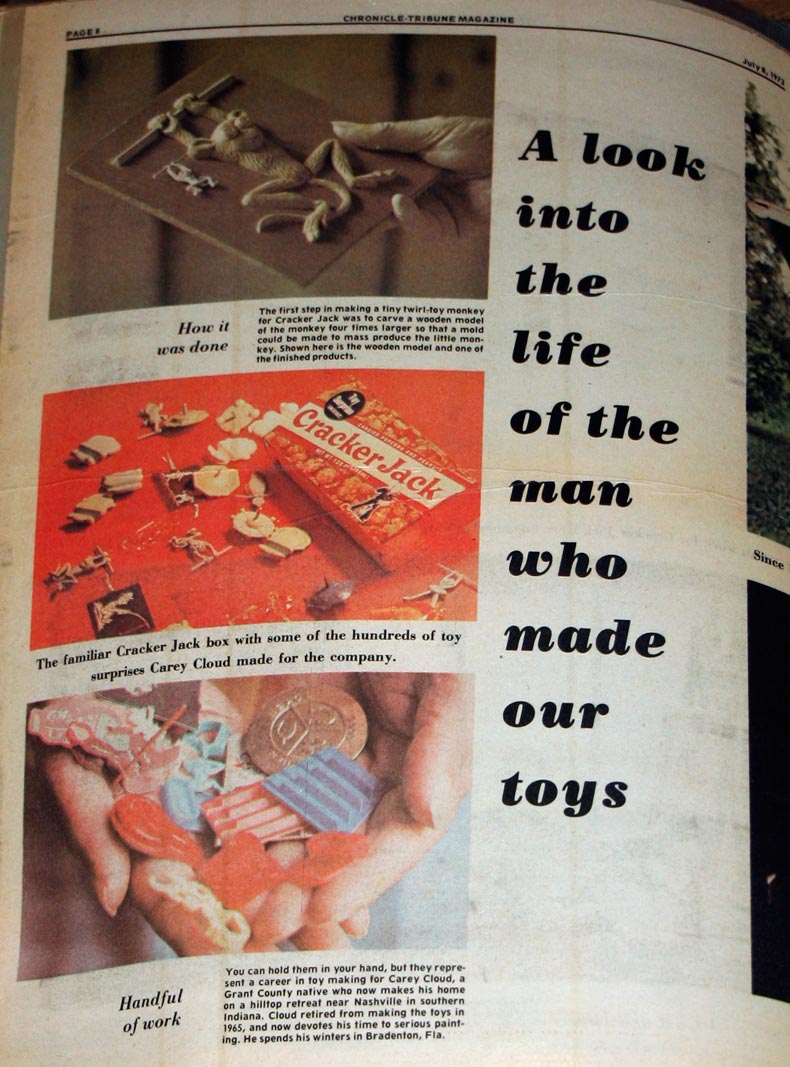

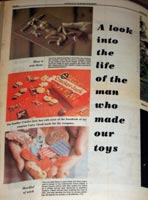

The first toy Cloud designed was a bobbing head tin animal. As times changed, it was

necessary for Cloud to find different materials and make different kinds of toys.

There was the switch to plastic, of course. But before that, during the Second World War, there was the problem of how to find metal, which was needed for the war effort.

He found the answer to his problems at the Ball Brothers plant in Muncie. In making the lids for the glass jars, the Muncie plant was ending up with two inch round piece of metal scrap for making the tops of jars.

"I bought those scraps by the ton; they were junk and there was no restriction on them." Carey Cloud had a plant working eight hours a day - stamping out goofy coins, daffy dollars, fake little amusing coins. One hundred million of them went into Cracker Jack boxes.

The Cracker Jack company had a rule, if there was one complaint on a toy it was to be thrown out. And in a quarter of a century, the toys produced by Carey Cloud only produced one did. "It was a little sea captain," Cloud remembers, "and

someone wrote in and said it looked like Stalin." The toy that looked like the Russian dictator was withdrawn

immediately.

There were lots of other letters. Letters from kids who wanted a toy just like the one a friend of theirs got in a box of Cracker Jack. (The company refused such requests since there were often 100 different toys being put into Cracker Jack boxes at the same time.

And there was a letter from a mother who said that she had been trying to teach her small son about God. She told him that God was responsible for everything that happened in the world.

"Oh," the youngster said, "so it is God that puts the toys in Cracker Jack."

"I got to thinking that this kid was right," Cloud says. "It was really done through a

Superior Being. And here I am taking credit for it."

Carey Cloud remembers one letter in particular. It was from a little girl in Kentucky. And it contained a small paper toy that, when connected, rocked slowly back and forth.

It was old and it was obvious that it had been used for days," Cloud says. "It had just plain worn through the paper."

The note from the little girl stated only, "It's broken."

Cloud packaged up more than a hundred different Cracker Jack toys and mailed them to the little girl. In a few days a letter came back from Kentucky. There were only two words. "Thank you."

Carey Cloud got more than thanks for his toys. He made a lot of money. Since he invented, produced and delivered the toys to Cracker

Jack, he could control all the factors. When he first began, Cracker Jack paid him $2.50 per thousand for the toys. The price later went to $3.50.

He had other interest. He designed children's books, greeting cards, he illustrated for some magazines, he designed and produced promotional campaigns for cereal companies.

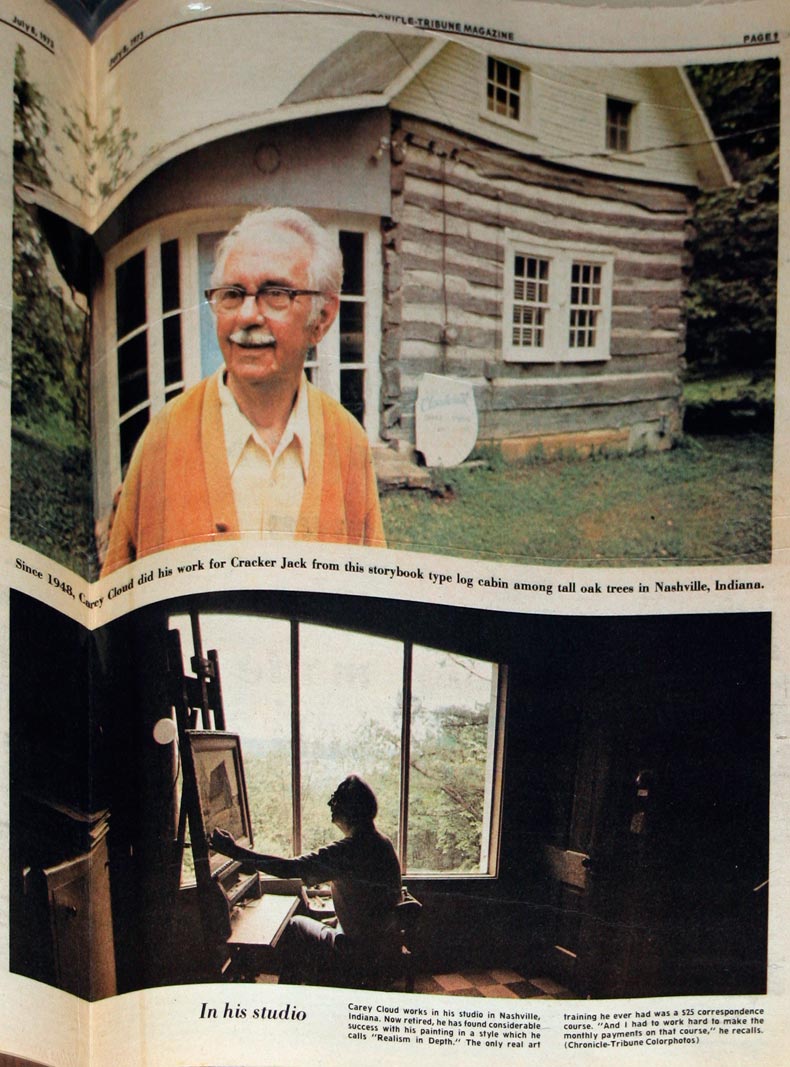

But all along, he held his interest in painting. In 1948 he moved to Brown County from Chicago, in the hope of finding more time for his painting.

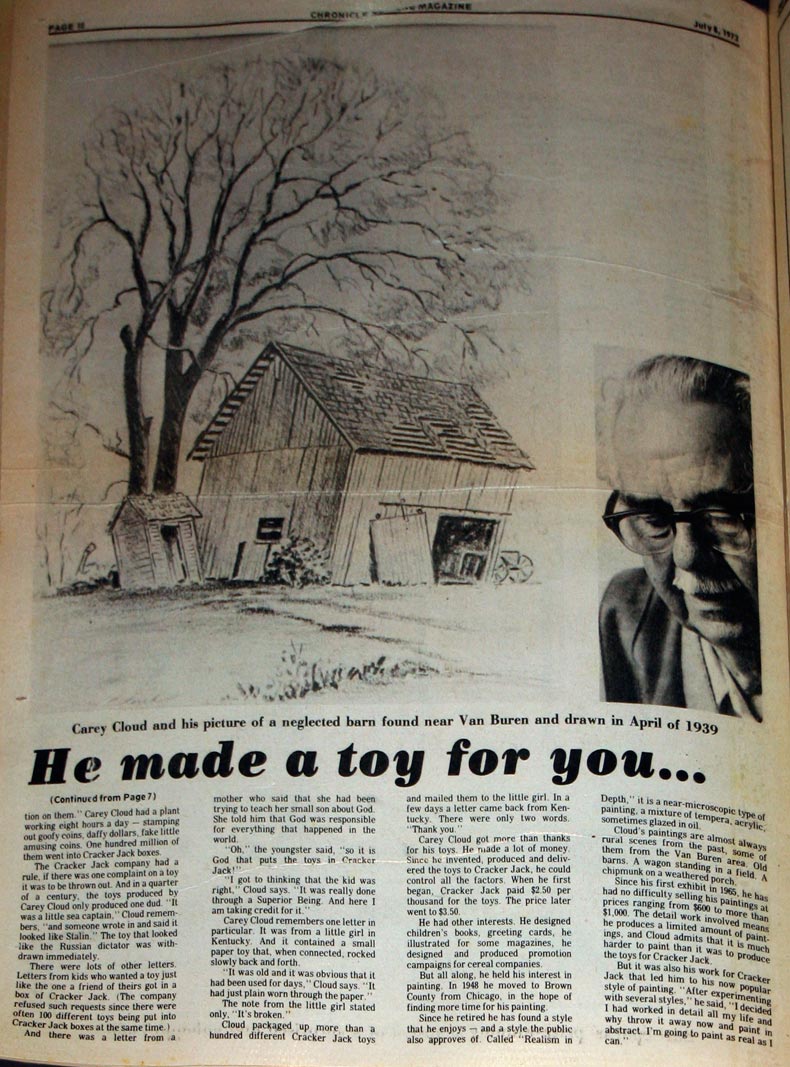

Since he retired he has found a style that he enjoys - and a style the public also approves of. Called "Realism in Depth," it is a near-microscopic type of painting, a mixture of tempera, acrylic, sometimes glazed in oil.

Cloud's paintings are almost always rural scenes from the past, some of them from the Van Buren area. Old barns. A wagon standing in a field. A

chipmunk on a weathered porch.

Since his first exhibit, in 1965, he has had no difficulty selling his paintings at prices ranging from $600 to more than $1000. The detail work involved means he produced a limited amount of paintings, and Cloud admits that it is much harder to paint than it was to produce the toys for Cracker Jack.

But it was also his work for Cracker Jack that led him to his now popular style of painting. "After experimenting with several styles," he said, "I decided I had worked in detail all my life and why throw it away now and paint in abstract. I'm going to paint as real as I can."